There is No Open-Source Higher Education Ecosystem

This is a post based on a talk I gave at HighEdWeb West 2016. View the slides.

Let’s create a web application.

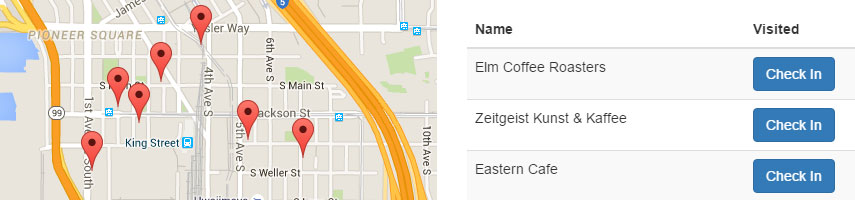

Specifically, let’s create a web application that generates a checklist of nearby coffee shops and displays them on a map.

So, what are our options?

Well, we could buy it: purchase a product that already meets our needs or find a vendor with expertise in building these types of applications. It might cost us, but at the end of the day we would have a complete, readymade application.

Alternatively, we could build it from scratch. Even for a simple application, there’s a lot to do: we’ll need a list of coffee shops around the world, someone will need to actually create the map graphics for us, we’ll need to style the user interface, and so on. We’ve got our work cut out for us (it could take years, even) but, in the end, we would have an application custom-built from the ground-up for our needs.

Or, we have another option: build part of it. Use a combination of open-source components, third-party services, and custom code to efficiently construct an application using building blocks, taking advantage of the past contributions of fellow developers. Integrate the Node Yelp client for quick querying of the Yelp database for nearby coffee shops, use the Google Maps Web Component for drop-in Google Maps integration, take advantage of Bootstrap’s robust UI library for front-end styling.

And, in fact, this is the approach most developers would take in building a modern application: search for open-source components that meet your needs, and build on top of them.

(I actually built this application, just in case you thought I was lying)

What About Student Systems?

Alright, I feel pretty good. We built ourselves a nice, little web application.

Let’s try something more challenging: let’s build a higher education student system. Specifically, let’s create a financial aid system.

Taking another look at our options:

Buy it. We could work with any number of financial aid vendors (Ellucian, College Board, Sigma) to develop a product that meets our needs.

Build it. Again, a lot of effort here developing code to capture all of the intricate financial aid business logic, but we end up with a solution that is custom-built for our particular requirements.

But, hey, wasn’t there a third option that worked well last time? Oh, yeah: build part of it, using open-source components as a foundation.

Why don’t we try that again?

The Open-Source Higher Education Landscape

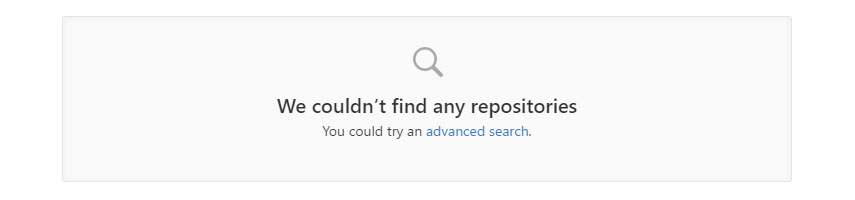

To get started, let’s see what’s out there for open-source financial aid components:

Nothing.

Wait, what? That can’t be right.

Maybe we just need to be more specific: instead, let’s look for open-source projects related to the Institutional Student Information Record (ISIR). This is a flat file that’s generated when a student completes the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA); it’s sent to higher education institutions that consume FAFSA data. So each school that consumes FAFSA data (or their financial aid system vendor) must parse this file format. Given its prevalence, there must exist an open-source library or two out there related to parsing or manipulating this file, right?

Nope.

What about open-source libraries focusing on the Common Record, another pervasive financial aid file format?

Nope.

Maybe financial aid is just cursed; what about common test score report file formats? Are there open-source libraries for handling the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) score report file format?

Nope.

Oh come on, what about the ACT file format?

Nope.

SAT? There’s got to be something for the SAT.

Nope.

We tried; let’s face it:

There is no open-source ecosystem for building higher education systems.

Kuali

At this point, you may be thinking: aren’t you describing Kuali?

Kuali is a suite of open-source higher education systems, including a student information system, an accounting system, and more. It’s a landmark achievement in the world of open-source higher education.

In other words, Kuali’s overall mission is to provide a complete, open-source end product for users, not a collection of modular components that can be mixed and matched.

All or Nothing

Kuali represents a typical understanding of open-source within higher education as a competitor to vendor solutions. Either you choose open-source or you choose a vendor.

I refer to this dilemma as the False Pizza Dichotomy of Higher Education Systems.

Let me explain.

In higher education, if you ask us to get you a pizza, we will say there are two ways, and only two ways to make that happen: order it or make it from scratch.

But, of course, we know this isn’t true: you could start with a premade crust, you could buy a frozen pizza from the store and add your own toppings, you could buy a take-and-bake pizza, you could buy a pizza kit with all of the ingredients included, and on and on.

It’s easy for us to list all of these alternative ways to make a pizza, because we can break down pizza into its parts: the dough, the sauce, the various toppings. We know how to build a pizza back up from those parts.

In the same vein, we need to break apart higher education systems. More precisely, we need to think small. Very, very small.

Instead of monolith systems, we need small, open-source higher education building blocks.

Why?

You may be on board with the idea of breaking apart monolithic systems, but why open-source?

There are a number of benefits to open-source development within higher education; let’s talk about three of them in particular:

Sharing the work. Naturally, if your system is openly available and used by other higher education institutions, each of these universities has a vested interest in seeing your project continue to thrive. An open-source project becomes a space for collaboration across higher education.

More eyes. Even if other schools are not able to directly contribute back to your project, by leaving your system out in the open, you provide more opportunity for other people to find bugs and suggest enhancements. In this way, open-source becomes a vehicle for constantly assessing and improving the quality of your project.

And, finally: more options.

Within higher education, the choice to either build or buy a new system often comes down to a choice between money or internal resources. Can we afford the vendor solution? Do we have the time and resources to roll our own system?

This places schools at a disadvantage: either we go with the vendor solution or we take on the burden ourselves.

This isn’t how modern application development outside of higher education works and we shouldn’t accept it within our world: we should have more freedom in how we build our own systems.

If we are dissatisfied with a vendor solution, we should be able to point to an open-source component in the wild and say, “Why can’t your product do this?”

We should expect that government departments and higher education organizations, like College Board, will provide libraries for consuming and manipulating the data they require us to consume and manipulate.

If we find a bug in a piece of software provided by the Department of Education, we should be able to help fix it.

We should be able to mutually benefit from the sweat and tears we are all currently pouring into building independent, isolated systems that live and die within our institutional silos.

What’s the Hold Up?

If it’s such a good idea, why hasn’t the higher education world embraced the sharing of small, open-source components?

In a word: bureaucracy.

First, bureaucracy begets bureaucracy.

Across higher education institutions, you see the same culture of bureaucracy: deep, complex organizational hierarchies combined with a staunch adherence to policy and procedure. Within this universe, the concept of small, modular components developed in the open clashes with the higher education culture. A bureaucratic organization wants to see itself reflected in its systems, wants to see a black box, enterprise-level solution from a vendor that was willing to trudge through a lengthy RFP process.

Choosing an approach to building systems that contrasts with the ideology of bureaucracy questions the traditional culture of the university system: if enterprise-level complexity isn’t a necessary component to building higher education systems, maybe bureaucratic organizational forms aren’t necessary for sustaining higher education either.

Second, bureaucracy is a safety blanket.

When discussing open-source in higher education, I often hear statements like the following:

That’s against university policy. Too bad the higher ups won’t go for that. It just won’t work here.

Statements like these distract from the real conversation: instead of talking about the specific benefits and challenges of open-source, we end up talking about the clash in culture between open-source and higher education.

So, what we’re really saying is:

This is something new and I have concerns.

And that’s okay.

Fear

Let me tell you something personal: I’m terrified of driving.

Basically, when I get into a car, I’m pretty sure I’m going to hit and kill someone. If you were tasked with reassuring me, what would you say?

One approach:

You’re an idiot. Driving isn’t scary. Get over it, baby.

But this isn’t helpful; even if my fears are unreasonable, they are still very real for me. And they aren’t unfounded: you can really hurt someone while driving a car.

And, on the opposite end:

You’re right; driving is scary. Never ever drive.

This isn’t helpful, either. Yes, you’ve legitimized my fears, but now I’ll never drive.

Instead, how about:

Your fears are valid, but we can address them by driving responsibly.

With this, you’ve respected my fears as legitimate without shutting down the opportunity for progress.

I bring this analogy up because it’s similar to approaching open-source: proponents of open-source will tell you that you’re stupid for questioning its benefits, while those fearful of open-source will tell you that it’s not even worth the trouble.

But we can strike a balance: we can take baby steps.

Baby Steps

Remember the false pizza dichotomy: we don’t have to choose between all open-source or no open-source at all.

We can think small.

For your first open-source project as a higher education institution, choose something:

- Small (really small)

- Useful (to you and other schools)

- Already Exists (not a new project)

This way, you don’t put a lot of additional work into making open-source part of your university culture. You just a choose a small, useful utility and put it out there. If more and more schools take these small baby steps, we can gradually build out an open-source ecosystem.

We can sample open-source, slowly folding it into the higher education culture.

As a concrete example: at the University of California, Santa Barbara Office of Financial and Scholarships, we have an open-source project called the Shopping Sheet. It’s a simple HTML template (13 files total) that allows institutions that offer financial aid to meet a Higher Education Opportunity Act (HEOA) requirement.

That’s it.

It’s not a new front-end framework. It’s not a new enterprise platform. We didn’t establish an official partnership with another school or a vendor to create it. It was something small and useful, that already existed, and so we decided to release it so other schools could use it and help us improve it.

Share Your Projects

While it’s true that the higher education open-source ecosystem is barren, it’s not completely empty. I know there are some useful projects out there and I want to hear about them.

Please, please send me your open-source higher education projects (big or small). Tweet at me or send me a message.

Let’s go out and collaborate with each other.